A koan is a riddle or puzzle that Zen Buddhists use during meditation to help them unravel greater truths about the world and about themselves. Zen Buddhism, Koans and enlightenment are intrinsically linked.

These succinct paradoxical statement or question used as a meditation discipline for novices, particularly in the Rinzai sect are intended to exhaust the analytic intellect and the egoistic will, readying the mind to entertain an appropriate response on the intuitive level. Each such exercise constitutes both a communication of some aspect of Zen experience and a test of the students competence.

The koan serves as a surgical tool used to cut into and then break through the mind of the practitioner… Koans aren’t just puzzles that your mind figures out suddenly and proclaims, “Aha! the answer is three!” They wait for you to open enough to allow the space necessary for them to enter into your depths—the inner regions beyond knowing.

Zen Buddhism Koans and Enlightenment

To study Zen is to embark on a path of learning to stop resisting reality, and in doing so to free oneself from superfluous drama and the ceaseless ebb and flow of mental states.

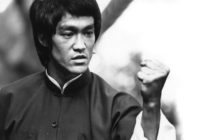

Here are some koans that I hope are particularly useful and relevant to your own spiritual and martial arts journey.

Flow Like a River

Flow Like a River

There is the story of a young martial arts student who was under the tutelage of a famous master.

One day, the master was watching a practice session in the courtyard. He realized that the presence of the other students was interfering with the young man’s attempts to perfect his technique. The master could sense the young man’s frustration. He went up to the young man and tapped him on his shoulder.

“What’s the problem?” he inquired. “I don’t know”, said the youth, with a strained expression. “No matter how much I try, I am unable to execute the moves properly”. “Before you can master technique, you must understand harmony. Come with me, I will explain”, replied the master.

The teacher and student left the building and walked some distance into the woods until they came upon a stream. The master stood silently on the bank for several moments. Then he spoke. “Look at the stream,” he said. “There are rocks in its way. Does it slam into them out of frustration? It simply flows over and around them and moves on! Be like the water and you will know what harmony is.” The young man took the master’s advice to heart. Soon, he was barely noticing the other students around him. Nothing could come in his way of executing the most perfect moves.

The Diamond Sutra

The Diamond Sutra

Out of nowhere, the mind comes forth.

The Way

A Master was asked the question, “What is the Way?” by a curious monk. “It is right before your eyes,” said the master. “Why do I not see it for myself?” “Because you are thinking of yourself.” “What about you: do you see it?” “So long as you see double, saying I don’t and you do, and so on, your eyes are clouded,” said the master. “When there is neither ‘I’ nor ‘You,’ can one see it?” “When there is neither ‘I’ nor ‘You,’ who is the one that wants to see it?”

Moderation

An aged monk, who had lived a long and active life, was assigned a chaplain’s role at an academy for girls. In discussion groups he often found that the subject of love became a central topic. This comprised his warning to the young women: “Understand the danger of anything-too-much in your lives. Too much anger in combat can lead to recklessness and death. Too much ardor in religious beliefs can lead to close-mindedness and persecution.

Too much passion in love creates dream images of the beloved – images that ultimately prove false and generate anger. To love too much is to lick honey from the point of a knife.” “But as a celibate monk,” asked one young woman, “how can you know of love between a man and a woman?” “Sometime, dear children,” replied the old teacher, “I will tell you why I became a monk.”

“MU”!

The final koan, I will share with you is MU. This koan is one of the most famous of all and is the one most often used by the leading Zen masters of today: Because of this, the Chinese/Japanese character for MU is sometimes displayed in the dojo or teaching space where Zen students gather.

Joshu (A.D. 778-897) was a famous Chinese Zen Master who lived in Joshu, the province from which he took his name. One day a troubled monk approached him, intending to ask the Master for guidance. As he was about to ask for guidance a dog walked by. The monk pointed to the dog and asked Joshu, “Has that dog a Buddha-nature or not?” The monk had barely completed his question when Joshu shouted: “MU!”

The character for MU literally means “nothing.” Joshu’s answer was quite simply “Nothing,” which was not to say that a dog lacks Buddha-nature. Naturally, both Joshu and the monk knew that Buddha-nature is inherent in all creatures without exception, which is why Joshu’s “MU” should never be interpreted as a denial of this fact.

The only purpose of his response was to break the monk of rational thinking in trying to understand the truth of Zen and to get him to aspire to a higher understanding of reality beyond affirmation and negation, in which all contradictions disappear on their own. Joshu’s “MU” is neither a yes nor a no. It is an answer that surpasses the opposition of yes and no and directly points to Buddha-nature, to the reality beyond yes and no.

(//peterspearls.com.au/the-zen-koan-mu.htm)

Flow Like a River

Flow Like a River The Diamond Sutra

The Diamond Sutra

1 Comment

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I have

joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your

wonderful post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social

networks!